"May none but honest and wise men": John Adams and the 'Making of the Presidency'

Review of the book "Making the Presidency: John Adams and the Precedents that Forged the Republic," by Dr. Lindsay Chervinsky. The book was published in 2024.

“I pray Heaven to bestow the best of Blessings on this House and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof.”

John Adams on the Executive Mansion—today known as the White House.

The United States presidency, as we all know, is a complicated office. Its legacy has developed, changed, regressed, and progressed. The idea of the office is pivotal in most history classrooms, as it is often the focus of how U. S. history is taught. Learning about history through domestic and foreign policy allows students to understand the depths to how presidents reacted to certain affairs. It helps students see the ongoing change through time, and connects them to someone they can represent themselves with.

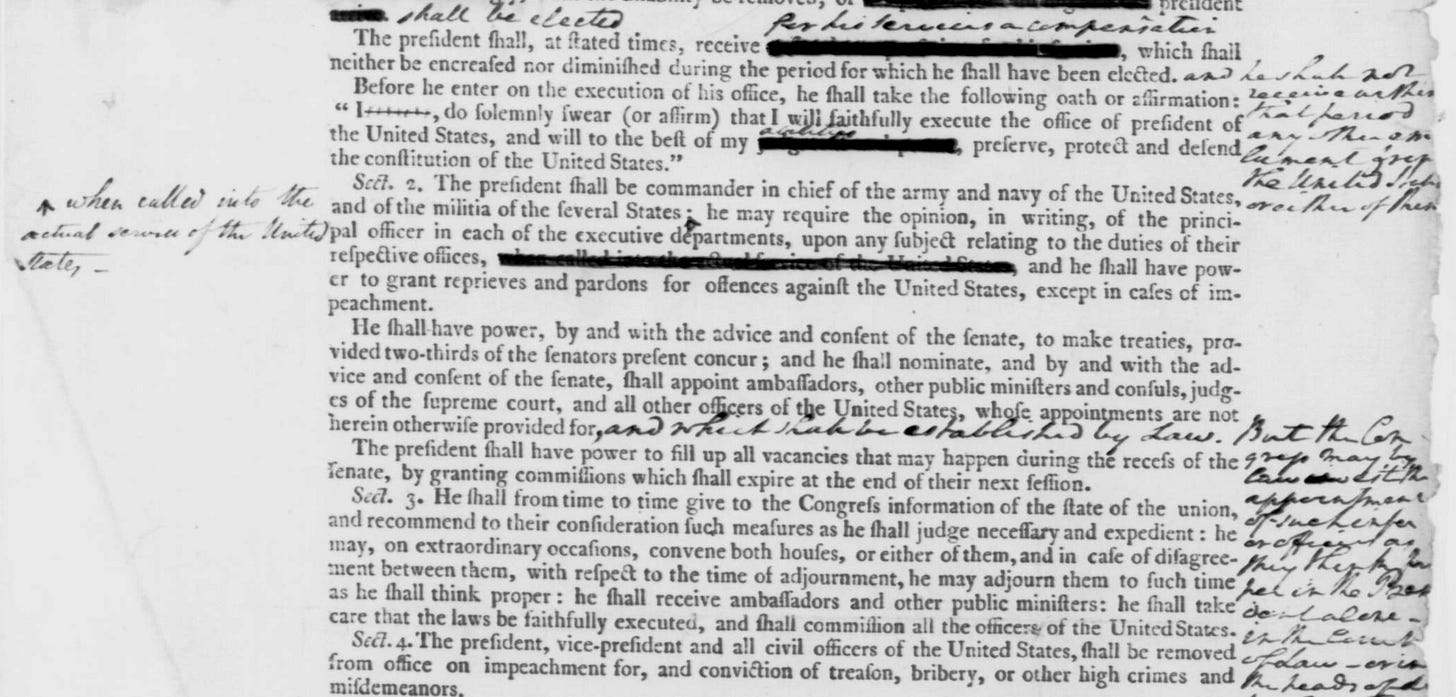

But in the beginning, the presidency was forged with large uncertainty. While George Washington was the first president, his administration was latent with unpredictably and cast with important questions. How will the president govern? What powers does he have? What powers does he not have? What will the relationship be to Congress? These and so many more questions were the focus of the Washington presidency. But arguably, the second president had the harder task. George Washington was always the vision for the presidential role. In 1787, at the Constitutional Convention, Washington’s copy of the Constitution is marked with extensive annotations under Article II (the section that details presidential power). Even Washington knew that he needed to prepare for the role of this new office.

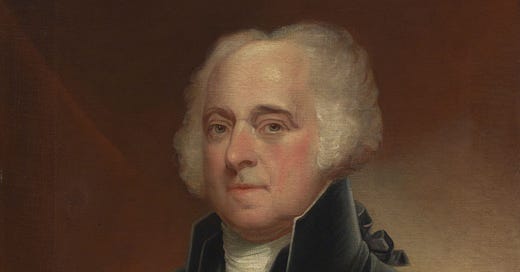

So when he announced his retirement in 1796, citing exhaustion and the yearning for his home of Mount Vernon, more questions arose. How will the United States survive without George Washington? Not if, but how? Who was a worthy enough successor? What happens if the country is unable to survive with strong leadership? John Adams, the second President of the United States, was no George Washington. Navigating the Republic post-Washington was a daunting task for anyone who followed him, and thus created a difficult period of mistrust and discrepancies amongst the people.

This navigation is the focus of Dr. Lindsay Chervinsky’s book, Making the Presidency, where she details John Adams as President of the United States and how he helped refine the template that Washington left behind. She writes that “Adams was tasked with navigating the presidency without that unique prestige… whoever came next was going to mold the office for all the chief executives to follow.”1 Chervinsky understands the power that John Adams held, and even more so, knows the quality of individual he was. Still, this does not let her blur the line between detailed statesman to complex president.

John Adams the man versus the president are two different people at two vital points in Adams’ life. I’d argue that the United States does not gain its independence in 1776 without the fierce defense of civil liberties and causations from John Adams. He transformed the story of the Revolution.

While president, Adams tackled a trade and naval war with France called the Quasi-Wars, which he tried to restrict the United States from participating in.2 Adams became fearful of French spies, and in response, signed the Alien & Sedition Acts. The Alien Act allowed him to “order all such aliens as he shall judge dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States.” The Sedition Act stated that anyone who wrote “false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States” would be “be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.”3 These acts are what has plagued his legacy, and many historians have tried to put it into context as much as they can.

Chervinsky pays special attention to not just the war and the acts themselves, but Adams and his thought process. Through letters and diaries, this book is an analysis of what Adams was thinking and why he thought it. Not so much a psychological history, but a political analysis of movements. She expertly puts Adams at the focus of every word she writes. While this seems like an easy task, it is quite difficult to make sure the main character is in every scene. Crafted with honesty, Chervinsky writes of the politics enabled by Adams:

President Adams had not asked for any of this legislation. He had not lobbied for it, nor had he instructed his cabinet to do so. And yet, one presented with these four bills, he signed them. He did not say why, but he wrote to Benjamin Chadbourne, a judge in Maine, "the fate of our republic is at hand.” Most republics fail when "the virtues are gone a free and equal constitution of government has rarely existed among men and requires constant vigilance to protect.”4

Writing history is a time consuming process. Formulating cohesive sentences and nuanced paragraphs that are digestible for anyone to read it is an art. Not to mention the crafting of sources, endnotes, bibliography, and index are all expected of an historian. Dr. Chervisnky makes this process looks easy. The books flows with consistency that it’s a breeze to read it. It took me two weeks to read it, and that is just because I needed to make annotations and notes. Minus that, it would take me no time at all.

Chervinsky has written one another book titled The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution, which was published in 2020. Both of her books were written in moments that we as a country needed them. My assumption was that her purpose was not to craft a book that directly correlated with the times, but I could be wrong. Her latest book informs us of the necessity with which John Adams worked, and how his presidency is a reflection of who we’ve become.

When John Adams lost the presidency in the Election of 1800, he ensured that the fundamental tribute of our nation was enshrined into the fabric of our Constitution. The peaceful transfer of power from one president to the next is part of the Adams legacy. John Adams did not attend his successors inauguration, not because he was a sore loser, but as Chervinsky argues, “there was no precedent of a defeated president attending his successors’ inauguration… Adams had not received an invitation to the inauguration and had no idea how his attendance would be received.”5 To be fair, however, Adams was bitter, and he was worried about his legacy and the presidency he left behind.6 But what it reveals to us is the necessary passage of the presidential torch.

Chervinksy’s wide breadth of sources are impressive; even more so are how she uses them. She interweaves primary sources that do not feel too invasive or distracting for the readers. Some may disagree, but quotes always strengthen the argument rather than weaken it. The jury is still out for a lot of historians on the excessiveness of quotes, but Chervisnky embeds them well here. She is an absolute master at the craft of writing history, and this is a book that deserves the time and recognition for how well it. I am probably biased because of my appreciate for Adams, but that is okay. I am grateful to have interacted with Dr. Lindsay Chervinsky on multiple occasions both in person and digitally.

Don’t wait on this book and go buy yourself a copy. If you prefer, there is an audio version that she reads herself!

BUY THIS BOOK: Chervinsky, Lindsay M. Making the Presidency: John Adams and the Precedents That Forged the Republic. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2024.

I do not make ANY money from using this link. It is here for your convenience.

Chervinsky, Making the Presidency, p. 2.

Chervinsky, Making the Presidency, pp. 170-173; Adams was unsuccessful in this endeavor as he was pressured from his own party to engage. Additionally, with the young nation, Adams did not want to jump to any conclusions too quickly. He relied heavily on advisors to help him make decisions as he wanted to ease the tensions between France and the United States.

Alien & Sedition Acts, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/alien-and-sedition-acts.

Chervinsky, Making the Presidency, p. 130.

Chervinksy, Making the Presidency, p. 332.

For my bachelor’s degree, every Senior was tasked with writing an original thesis paper. My thesis focused on John Adams and his retirement. The paper argued that John Adams own lack of self confidence was fueled by the press and made him unconvinced of his place in history. Looking back, it is quite the broad argument, but I was passionate about it. I wanted to look at how Adams was showcased himself in retirement because he had twenty-six years to reflect on his life. He came to the conclusion that it was not worthy of talking about, and that deeply interested me. Adams became a really interesting character for me, as I spent two years of my life with him and his letters. He is the reason I study Early America and Republic. If anyone reading is interested in reading it, I am happy to send a copy over.

Great first edition, my friend. And superb analysis of a timely and important book!